The site of Villawood Detention Centre embodies the transformation of federal immigration policy in Australia. This is a series of personal stories from people who lived in Villawood during its different incarnations—from its first imaginings as a place to house immigrants after World War Two, to its present status as a detention centre; described by those inside as ‘’worse than a prison.’’

Roaming around the parameters on a bright afternoon, the detention centre often embroiled in human rights controversies is strikingly close to day to day living in Sydney’s western suburbs. Backyards wreathed by the Australian flag fall away into a tangled gulley of barbed wire fencing. An elderly couple tenderly hold hands sitting on plastic chairs on their verandah; behind them a panoramic view of the lime wash facilities. From a distance, no movement can be seen inside except a lone guard making his way across the complex, head down. It is surprisingly quiet. A magpie warbles.

Villawood Detention Centre is currently home to one of Australia’s darker policies. Whilst Australia has rightly faced international criticism for its inhumane ‘offshore processing’ of asylum seekers on Nauru and Christmas Island, trauma can also be found closer to home.

The majority of asylum seekers -- 2,394 -- are currently detained in mainland centres. Many have been incarcerated with no charge; others have been in detention over five years with no access to information about their terms. The psychological abuse is taking its toll -- a study released in October of this year stated at least one in four refugees locked in indefinite detention has attempted or threatened suicide. Lawyers have described their state as legal limbo similar to that in Guantanamo Bay.

Villawood is Australia’s second largest mainland detention centre, yet it was not always designed for locking up people. Mandatory detention was only introduced in Australia in 1992 and before then, asylum seekers lived freely in the community. Villawood was originally built in 1949 with the opposite intention – as a migrant hostel to attract immigrants to come and stay as part of a nation building project.

Villawood is an important site that has contributed to the growth of Greater Sydney and reflects both the expansion and contraction of the borders of national belonging.

“It was a nice, friendly place that greeted us with an open heart; it was a good start to Australia.”

Izabel lives in Padstow. She worked as a beautician in Ashfield for many years and now has two children both in high school. She stayed at Villawood when she first arrived in Australia in 1981. When migrants left the Villawood Migrant Hostel, many chose to stay and settle in the Greater Bankstown area and the development of many western suburbs was a result of the post-war migrant boom. Izabel was part of the ‘second wave’ of Polish migrants who came during the 1980s before Polish Solidarity ousted the communist government in 1989.

The first wave of Polish migrants arrived in Australia after World War II when Villawood was originally dreamt up as a Migrant Hostel to accommodate displaced persons and assist migrant resettlement. During this post-war period, Villawood was internationally advertised as a place to come and stay as part of the Commonwealth’s nation building project. The government wanted migrants to come from abroad. The threat of invasion by Japanese forces during the Pacific War exposed Australia’s vulnerability and isolation from strong allies – and the government was looking to increase the population. At this time, Australian immigration was dominated by the White Australia Policy, so the targets of the campaign were British and European subjects. The government of the day used propaganda tactics to entice immigration to Australia, playing on the wide open spaces, and the sense of opportunity that going to a new land can bring.

Between 1947 and 1953 over 170,700 displaced persons arrived in Australia. As part of theircontract, displaced persons had to stay in Australia for at least two years and in that time were bound to work in whatever job they were placed regardless of prior skills and experience. In return they received hostel accommodation, unemployment benefits and access tofacilities for learning English. By the late 1960s more migrants began arriving from South America, Turkey, Lebanon, Spain, and Czechoslovakia. The ‘second wave’, like Izabel, left Poland because they didn’t see a future for themselves in the country.

“At the time I was there [Poland], there was only vinegar on the shelves in the supermarkets. You had to queue up for one roll of toilet paper... Three days to queue up for a fridge. My friend’s family took it in turns to stay in the queue in shifts. We knew the world outside had much more to offer. For me, I wanted to travel. I wanted to work. I wanted to be able to buy clothes. I wanted to feed myself in a normal way. I wanted a better life.... It was hard…. but for most of the people we embraced Australia. We could go to work; we were able to set ourselves up within one year with beds, TVs, fridges. In Poland it would take years and years to get this. Migrant or not, you had equal money in Australia and you could save for these things.”

Migrants from the earlier period remember the poor conditions at Villawood; the flimsy partitioned walls, the stink and the extreme strain it placed on families. But they also remember roaming around freely and walking down to the local shops to buy drinks and cigarettes.

“There was no such thing that you could not leave,” says Izabel. “We were entitled to social benefits straight away. It was fantastic – you are a foreigner and were given some small money for cigarettes, lollies, travel. People would go to the ocean or church, walk in the evening with the cicadas and the light bright outside.”

Izabel says there was some tension. She remembers she had to sign a form in Vienna before she arrived, stating she would not discriminate against the ‘boat people’. At that time the ‘boat people’ were Vietnamese fleeing the communist regime. But she says there was certainly no electrically charged barbed wire, no guards searching their rooms and, most notably, they could walk out of the gate when they decided to start their new lives.

“I was only there for a week. My aunt came and she said, ‘you need to start normal living’. And I thought, yes, that is what I want, just normal living. We come to a new country to start a new life. You are filled with energy and ideas but also some shock. And if you have to wait, the energy and the ideas gets smaller and smaller; if you wait there is no way to move beyond the shock and you get depressed.”

Izabel says most people embraced the Australian life and the opportunities they wouldn’t have had in Poland. She is saddened by the different reception refugees are met with now compared to when she arrived.

“When I hear about the refugees now I always think about how I was there. I feel sorry for the people. It is good to have a place to come to, but I cannot understand why those refugees have to stay in the centre for that long. It is absolutely demoralising. I don’t know how these people survive.”

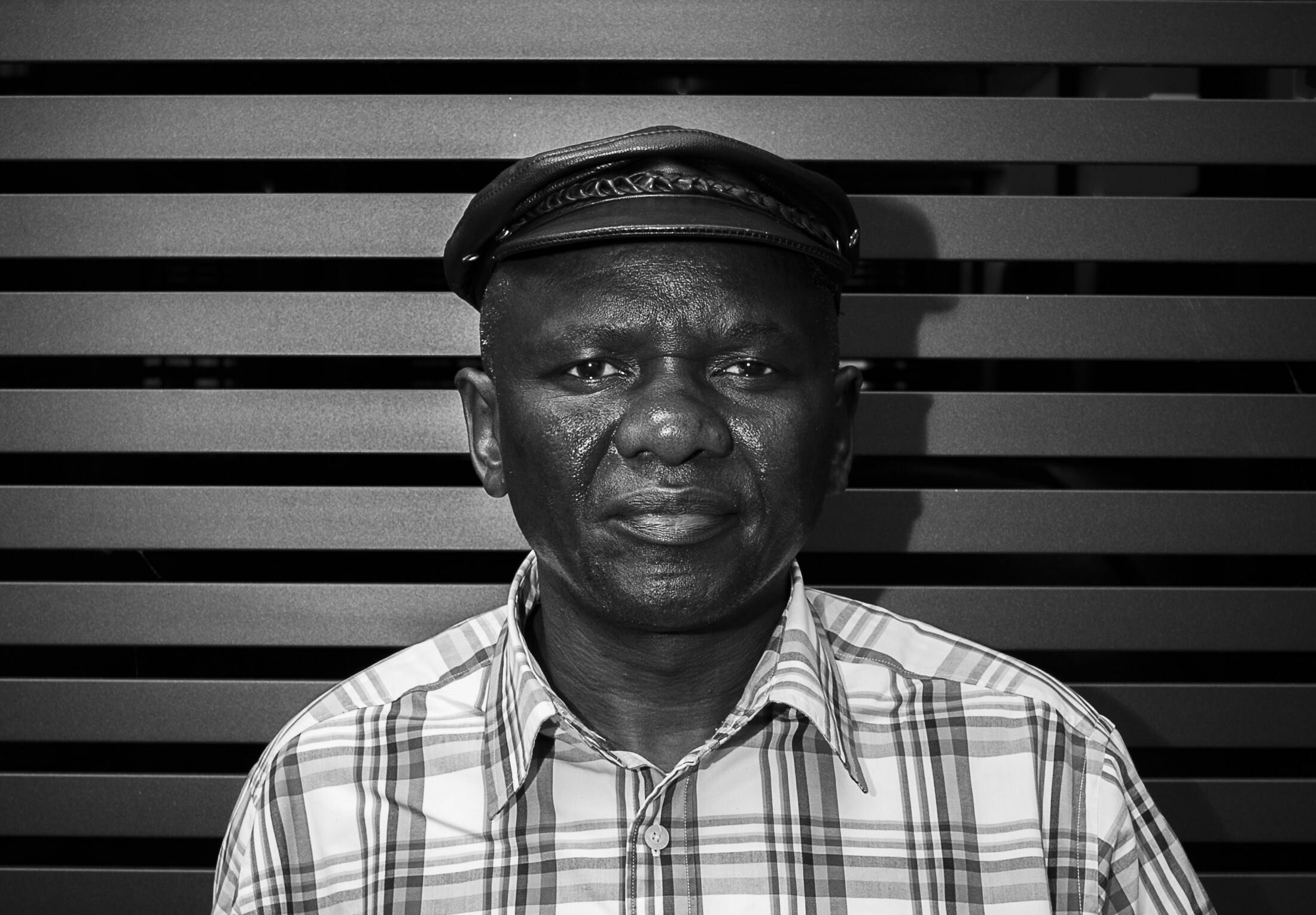

“I know it is not my country, but every time I think back to my time in Villawood, I wonder why they had to lock me up like I had done something wrong.” -William.

On the morning of 1st April 1998, I was asked by Australian customs, ‘where are you going Mr Williams?’ I was wearing a blue suit and looked very nice and young. It started well. My friend has arranged a Business Visa and we had established a story that I was a building engineer coming to Australia to buy materials. But as the questions continued it was clear they did not believe me and I had not been expecting this. They asked how much money I had. I only had one hundred dollars in my pocket. They asked where I would be staying. They threatened to deport me and I didn’t know what to say. Finally they opened my bags and inside were my army photos and medals. The girl became emotional. She asked me, ‘are you running? Were you a child soldier?’ I didn’t know how to answer this. She told me quietly it was different if I am running. She said I would be allowed to stay but they would need to hand me over to immigration. And then I was locked up in Villawood.”

In 1992 Mandatory detention was first introduced in Australia. Until this period asylum seekers and refugees has been allowed to live freely in the community. The detention policy was first introduced under Labor Government in 1992 in response to a wave of Indochinese boat arrivals. These measurements were later increased under the Pacific Solution – which closest resembles the current policy– when unauthorised boats from the Middle East began seeking asylum. “We heard a long time ago people weren’t locked up (in Villawood) and they could leave for the day. They (the government) gave them money and let them go into the community to buy things and come back. But when I came in 1998 the gates were definitely closed.”

William was born in Uganda. When he was fifteen he was recruited by the Uganda Freedom Movement (UFM), the national resistance movement to fight against the government regime. At the time, Milton Obote was ruling the country in his second term of government, an era which Amnesty International estimates was responsible for more than 300,000 civilian deaths across Uganda. “Parents and friends, and everyone want you to join the rebel forces. They (UFM) came to my school while I was studying and they tell you what you want to hear – they talk about the future. It all starts because the governments are so bad, people want change. Friends come and recruit, and this is the thing, we knew each other within the community. When you join these guerrilla outfits they promised us when the war ends they will give us scholarships to go back to school in good schools, overseas. You feel you are going to have a future in your country. But children are easy to manipulate – they are quick to learn everything, and take orders. And we did.”

Through the 1980s the UFM fought in the bush, led by Museveni. When Museveni came to power in 1986, William suddenly found himself fighting for the side of Government forces. “When we were in these rebel activities– we had a hard life and suddenly (when Museveni came to power) these guys gave us everything. I had guns, I had smokes, and I had all the beer I wanted. I had power. If I decided you live today, you live. If I decided you don’t live, you don’t. That’s the life we were in. They empower you, brainwash you and you think you have everything.”

Initially Museveni promised them everything they wanted, good governance, the end of sectarianism, and transparency. It was only later when they looked at what he’d done to Uganda they began to realise how corrupt and destructive he was. William and his friends decided they would overthrow Museveni and they began to plan a coup. By this stage William was a high ranking lieutenant and he had access to weapons as he used to transport the arms from helicopters to the trucks. He says they held meetings in the city and mobilised other dissatisfied groups to hatch their plan.

At one in the afternoon, on the day they were planning to carry out the coup, they were discovered. “We were out in the open but I saw the formation of the army coming as I knew the formation of army battles. I told the others we were surrounded. The others didn’t believe me but I said I am running. I heard people cry ‘stop’ but I just kept going. Then I heard the blip… blip… of the guns firing. Rain started. I heard people screaming. I remember rain, rain, rain. I took off my shirt and tags and hid underneath a small farmhouse. I caught a taxi back to my village to check with my mum and tell her what has happened. At this time my first child was born. I said I think my life is in danger. In the morning the newspaper story came out with all our names. Six people were arrested and the rest of us at large. There was an arrest warrant and an order to shoot me at sight.”

His friend organised for him to leave the country and obtained a visa, a passport and a one way ticket from the high commission in Nairobi. There was no time to say goodbye. “When I went to Villawood, I went through screenings. They asked me about my bullet scars. They took photos, fingerprints. They did medical check-ups, took my saliva. I was allocated a room. Goodness. It was like a prison.” There were people from Iran, Albania, Iraq, Ghana and Nigeria. I was the only Ugandan so there was no one to speak with. All the rooms had cameras. It was so strange coming from a fighting, active background to this. I did military drills in the basketball courts to keep fit each day. But there were other people who didn’t leave their rooms and just watched me. It was so hard to get outside information. People all kept saying different times – you will be here two months, or one year. They allocated a lawyer and interpreters who told me I had to have a good story. People were being taken out and back to their country all the time and the lawyer said their stories were not strong enough. Was my story ‘good’? I didn’t know what this meant.”

William was in Villawood for six months. “You ask yourself when you are in there. Am I a prisoner? Am I a refugee? I thought it was bad. But now it is worse, much worse, with this Cambodia deal. I have to think I was very lucky.” William now works as a nurse in a retirement village. “I spent a lot of my life fighting. I like this work, being given the opportunity to care for people. I am happy now.” But he is critical there is no continued support offered for refugees and asylum seekers once they are ‘released’ into the community. “I think there should be a proper way of moving people into the community. Keep monitoring them. It is emotional to leave your country, to go through a war, to go through this time in the Villawood camp, and then to go into Australian society. I tell you, during my time in the army, these are guys born into the Revolution. Some of us started fighting when we were 7 or 10 years old –these are guys who don’t know what else to do as they spent their whole lives as soldiers. What I saw in Villawood is isolation.”

“This is the dark side of Australia. This is the side they don’t want to tell the world.”

It has been a year since Abdul was released from Villawood Detention Centre. We meet at his house in Sydney’s inner-west where he lives with his new wife and her family. He is polite, gentle, and courteous as he answers questions. But his twitching jaw muscle belies his tension. He has asked not to be named and is reluctant to give any specific details that might identify him in the face of his pending visa application. “Can you please not include that comment, it is too detailed………please no photos of my face.” We ask if we can take a photo of his hands. “No.” His answer is clear. It makes the interview difficult.

There are hundreds of refugees in a similar position to Abdul, released into the community on bridging visas which come with strict conditions attached. Under the latest deal introduced last year, refugees in Australian custody on TPV or a five-year “safe haven enterprise visa” (SHEV) are not allowed to work, are provided with limited financial assistance, are barred from seeking family reunion and will not be allowed to re-enter Australia if they leave. Talking with the media is not advised. Refugee rights groups are concerned the so-called reforms will leave thousands of refugees as a permanent underclass, deprived of the possibility of residency, citizenship or the possibility of reuniting with their families. Despite all this, Abdul is more scared they will send him back to Villawood.

Abdul left Afghanistan in 2000 when the Taliban increased violence and persecution against his family who are part of the Hazara ethnic minority. Since about 1998, a significant proportion of boat people coming to Australia have been Hazaras from Afghanistan or Pakistan. The Hazara people, the majority who follow Shiite Islam — have been targeted by the Pashtun (Sunni) majority in Afghanistan for a long time, but animosity towards the Hazaras increased during the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan and ethnic cleansing became especially heightened under the Taliban.

Under Taliban rule, Abdul’s felt his life to be in critical danger. He fled the country and spent the next ten years moving between Greece, Italy, and France - always on the move and unable to secure proper work or a livelihood without a visa. In 2010, he left for Australia. On arrival, immigration officers spent two days questioning him and he was placed in Villawood Detention Centre for the next three years.

Villawood flared up as a site of controversy during Abdul’s time there when, in April 2011, detainees set fire to nine buildings and occupied the rooftops of other buildings in protest. The Immigration Department (caps?) says about a quarter of the 400 detainees were involved in the protest. The riot police were called along with a police rescue squad, the dog squad and about 100 fire-fighters. Standing on a rooftop were four protestors holding a banner, ‘We Need Help’. One detainee told The Sydney Morning Herald he felt powerless, “I’ve been in the detention centre for 20 months. I’m not an animal, I’m human.” Abdul said the asylum seekers were kept locked up in a separate section and on that night no one came to help them to escape the fire. “Inside it was very complicated. Lots of gates that led to other paths and all were controlled by a master key. On that night all the doors were locked and no one could get open any of the doors while this fire was blazing outside. The guards just took the master key and fled and left us there. The thing is,” he says, “We (asylum seekers) never tried to escape as we have nowhere to go. We don’t want to run anymore. We have wasted too many years running. We just want to live legally and get on with what is left of our lives.”

A multinational service company called SERCO run all the detention centres on Australia’s mainland. Many people in Villawood have been incarcerated with no charge; others have been in detention over two years with no access to information about their terms.

“A prison sentence would have been easier,” says Abdul, “At least in prison they tell the inmates how long their term is for. It is the not-knowing and little distraction that breaks you.” The routine for the ‘clients’—the Australian Government’s official term for detainees—involved daily head counts. The officers would come early in the morning and late at night. Abdul says, rooms were searched fortnightly and they would confiscate any recording devices, mirrors, sharp objects and personal property. Apart from this, there was a gym with little equipment they could use. There were English classes held four times a week, which Abdul attended. Otherwise there were no other distractions. He says with nothing to do to keep peoples mind off the situation they went into themselves. "Many mornings’ people won’t get out of bed or they walk around in circles as they have no reason, no purpose anymore.” Abdul said it didn’t come as a surprise that during the three years he was incarcerated about sixty people tried to escape. “There were three fences you had to jump over; the first was about two metres, then another one at three metres and then a final four metres that would catch people. But still, some were successful.”

Abdul says he was one of the ‘lucky ones.’ He fell in love with one of the visitors that came to the centre as part of a volunteer group offering ‘diversion therapy’ on a weekly basis. They got married and he now lives with her family. We (I ask – when was it we?) ask about the moment the realised they were in love? Abdul’s jaw muscle twitches again. He doesn’t want to talk about the new love, as the Australian government does not look up personal relations between ‘clients’ and visitors favourably. Abdul says he is happy to be out and with his new family. But he is worried because the entire family have now incurred such significant debts from the ongoing visa process he is unsure if he will ever be able to economically start a life with his new wife. He gets up to shake our hands, signifying that he is tired and that our interview is over. His hands are dry and cool. “For all the talk of ‘boat people’ it is ironic,” Abdul says as he shows us to the front door, “because the inside of Villawood reminded me of the shape of a boat.” The whole time he was at the centre, he says, he felt he never got off those rocking waves.

*Names have been changed to protect identities.

Like this story?